Faster Than Light is such a good game in a lot of ways, but I’ve noticed something about it that bothers me. The morality of Faster Than light is… complicated. Your mission is at once simple and insanely difficult, get the top-secret information to the Federation without being caught by the advancing Rebels or destroyed by the many other dangers of the universe. Within the scope of this larger mission it becomes easy to justify actions for the greater good. You don’t have to give out fuel to stranded strangers. You don’t have to save people from a burning space station. You don’t have to intervene to attack slavers or pirates. Further complicating this is the fact that it’s unclear what the Rebels or the Federation stand for, the immediate moral conflicts seem more real than what the game tells you is the actual objective. Which you will probably fail at anyway.

Further complicating things is the fact that the game often doesn’t punish you for doing something morally wrong. Sometimes it does, but more often it doesn’t. This absence of a mechanic is in itself a clever choice, it gets across the feel of an uncaring and uncertain universe perfectly. Even better, the game is teaching you to behave immorally, something that could bite you in the ass later on. However, where this falls apart is with the emotional lives of your crew. Sometimes you will decide on a morally reprehensible course of action, and the game will note that your crew is not happy about this. This doesn’t translate into gameplay at all. This is where the game should take a leaf out of the book of Darkest Dungeon, and make it possible for your crew to get stressed out or angry.

The universe of Faster Than Light is vast, and everywhere you travel you meet with unrest, slavery, disease, piracy, asteroid field, former allies who turn on you, rebels who want to kill you for ill-defined reasons, and cool sounding tourist sites you don’t have the time to visit. This is not a place where going about your job should be easy. At the moment, the only way the journey changes your crew is that they learn new skills, which immediately becomes useless when you find an alien who already has that skill maxed out. This game mechanic treats your crew like objects. Like your ship’s weapon or shield systems they’re there to be upgraded and fixed when damaged. Wouldn’t it be more interesting if by making immoral decisions, you caused your crew to question whether they’re on the right side at all. It would also make your punishment for bad behaviour cumulative rather than random.

One place where these moral mechanics are really necessary is when you encounter slave traders. As depressing as the Faster Than Light universe is, slavers might be the most reprehensible thing in it. The only way to stop slavers is to destroy their ship, which is no solace to any slaves who were onboard. You can choose not to attack, or alternatively you can buy one of their slaves and free them to work in your crew. This raises all sorts of moral questions. If you buy someone, and they are expected to work in your crew, and you don’t have an option to take them home, are they really free at all? I’m not suggesting you should be able to keep slaves, and perhaps in this savage lonely universe an inevitably doomed fighter ship isn’t such a bad place to be. But I think you should have the option to return former slaves home, and if you don’t they could reasonable feel quite upset about that. Having every freed slave pull a genie from Aladdin on you is a little too neat.

These emotional mechanisms would really be amplified when faced with the tensions between alien races. There’s an event where a Zoltan ship is attacking a Mantis one and will soon destroy it. In theory, the Mantis are ruthless enemies, and the Zoltan are your allies albeit somewhat overzealous with their laws. However, in the unrest brought on by the Rebellion, the Zoltans are nearly as likely to attack you as the Mantis. There’s also a romantic appeal to joining the wild Mantis on the losing side, against the uptight Zoltans. This is a wonderfully crafted and instantly engaging dilemma. But what is really interesting about this situation is that no matter what you decide, the Mantis and Zoltan members of your crew are unfazed by you choosing between their two races.

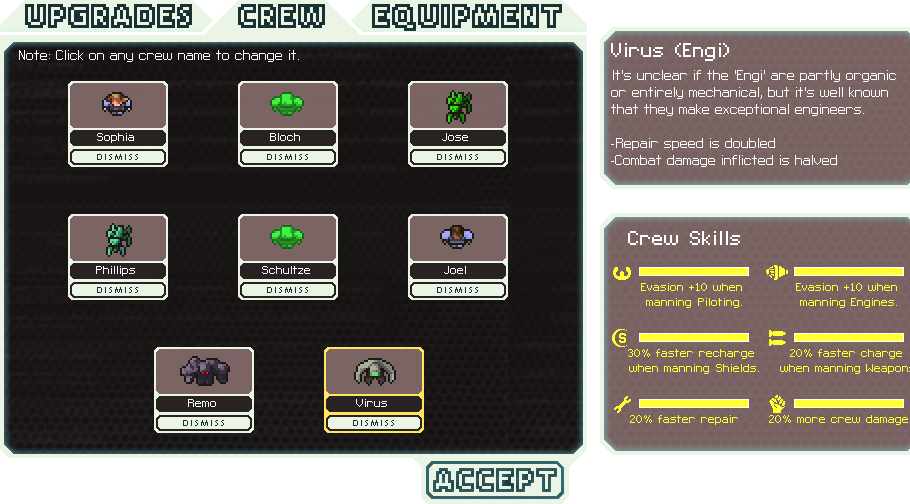

Given that the Mantis are so warlike and dangerous, it would make sense if your crew generally felt uneasy about working with them. In another event a virus infects and destroys a member of your crew, one of the mechanical Enji. after you defeat an Enji ship trying to destroy the virus, it reconstitutes his body with the virus’ consciousness and joins your crew. While this new virus crewmember has excellent stats, this would undoubtedly trouble any other Enji crew. In theory the Enji don’t feel fear, and yet they have enough self-preservation to try and destroy your ship with the virus on, why wouldn’t they try to kill the virus crewmember out of fear of infection? And what about other emotions? Can the Enji feel love or grief?

There’s an achievement you can get when playing as a Kestrel Cruiser called the United Federation. It’s a major part of unlocking more advanced Cruiser designs. You get the achievement by having 6 crew-members from different alien races. At the moment, all this means is having enough money and visiting enough shops, until you have bought yourself the necessary crew. This, I feel, misses the point. Unity is hard, and the mechanics should reflect these tensions. We see this in the fall of the Federation which, the achievement implies, held up the ideal of unity ideals. In addition, most sectors of space you pass through do not belong to the Federation anymore, they are divided between the various alien races. Unity is hard, but as each of these races has something to offer, it’s something worth working for.